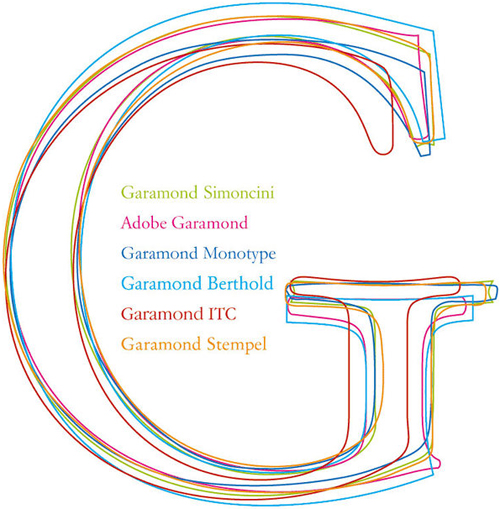

Garamond v Garamond

a mill for making paper

“The invention of paper is credited to Ts’ai Lun, a Chinese, in the early years of the second century. . . .

It took a thousand years for Ts’ai Lun’s idea to reach Europe. In the interval paper was produced in Japan, early in the seventeenth century. In the eighth it appeared in Samarkand; the process is though to have been picked up by Arabs from Chinese prisoners. The Moors may have carried paper-making into Europe. The year 1085 is given as the date of a mill for making paper at Jativa, Spain, that produced a rag sheet, chiefly of linen fibers.”

–Warren Chappell, A Short History of the Printed Word, 1970.

variations on a theme

“One logical and rewarding way [to consider roman type] is to think of the forms as a series of geometrical variations on a theme of square, circle, and triangle, which, when set together, will become a frieze of contracting and expanding spatial interruptions. This breathing quality is the very essence of the inscriptional concept, and is responsible for the liveliness as well as the nobility of the great classic carvings. Almost every letter shape carries its contained space, which in type is called the counter, and which is related, in composition, to the separations between letters. This inner space is not only vital to the color of a form—its black-and-white value—but is also an integral part of it.”

—Warren Chappell, A Short History of the Printed Word, 1970.

A serif

“A serif is a terminal device, functionally employed to strengthen lines which otherwise would tend to fall away optically. This is especially true of incised lines. By using a chisel in such a way that the finishing cuts were wider, a craftsman produced a strong terminal with a bracketed appearance.”

—Warren Chappell, A Short History of the Printed Word, 1970.

Roman [type]

“Roman [type] has come to be divided into three categories. Those having calligraphic stress and bracketed serifs are old style. Romain du roi was the forerunner of the types called transitional. The third category, modern, is applied to those alphabets, starting with Bodoni’s in 1790, which have lost all relationship to written models.”

–Warren Chappell, A Short History of the Printed Word, 1970.

stereotype

“As early as 1727, William Ged, of Edinburgh, invented a means of pressing a type form into material that could then be used as a matrix to make a casting duplicating the form. Ged’s invention was strongly opposed by the printers of his time, but in 1794, Firmin Didot became interested in the machine and experimented with the inventions of Ged and others. It was Didot who gave the process its name: stereotype, the prefix ‘stereo’ describing the solidity of the printing unit.”

—Warren Chappell, A Short History of the Printed Word, 1970.

‘I believe in the Book of Kells!’

“I recall Edward Johnston as a serious and courteous man, weary from ill health, but with a startling and delightful clarity of mind. He was a perfectionist. Once, too briefly and inadequately, I said to him that I did not believe in perfection. His immediate response was: ‘I believe in the Book of Kells!’”

—Alfred Fairbank; quoted by Warren Chappell in A Short History of the Printed Word, 1970.

Littera scripta manet

“Littera scripta manet—‘the written word remains.’”

—Horace, his motto; quoted by Warren Chappell in A Short History of the Printed Word, 1970.

the number 26

“Ever since the invention of alphabetic writing by the Phoenicians (or at least, by a northwestern Semitic people) in the second millennium BCE, letters have been used for numbers. . . .

Given their alphabets, the Greeks, the Jews, the Arabs and many other peoples thought of writing numbers by using letters. The system consits of attributing numerical values from 1 to 9, then in tens from 10 to 90, then in hundreds, etc., to the letters in their original Phoenician order. . . .

In these circumstances, every word acquired a number-value, and conversely, every number was ‘loaded’ with the symbolic value of one or more words that it spelled. That is why the number 26 is a divine number in Jewish lore, since it is the sum of the number-values of the letters that spell YAHWEH, the name of God.”

—Georges Ifrah, The Universal History of Numbers; from Prehistory to the Invention of the Computer, 2000.

the ‘five-barred gate’

“Everyone can see . . . sets of one, of two, and of three objects . . . and most people can see . . . set[s] of four. . . . Beyond four, quantities are vague, and our eyes alone cannot tell us how many things there are. . . .

The eye is simply not a sufficiently precise measuring tool: its natural number-ability virtually never exceed four. . . .

Perhaps the most obvious confirmation of the basic psychological rule of the ‘limit of four’ can be found in the almost universal counting-device called (in England) the ‘five-barred gate’. It is used by innkeepers keeping a tally or ‘slate’ of drinks ordered, by card-players totting up scores, by prisoners keeping count of their days in jail. . . .”

—Georges Ifrah, The Universal History of Numbers, 2000.