the River of the Dead of the Choctaws

“The paths made by deer and bear became roads and then highways, with towns in turn springing up along them and along the rivers Tallahatchie and Sunflower which joined and became the Yazoo, the River of the Dead of the Choctaws—the thick, slow, black, unsunned streams almost without current, which once each year ceased to flow at all and then reversed, spreading, drowning the rich land and subsiding again, leaving it still richer.”

—William Faulkner, ‘Delta Autumn’, Go Down, Moses, 1942.

the great blue dog

“[F]rom time to time the great blue dog would open his eyes, not as if he were listening to them but as though to look at the woods for a moment before closing his eyes again, to remember the woods or to see that they were still there. He died at sundown.”

—William Faulkner, ‘The Bear’, Go Down, Moses, 1942.

Airedale

“‘He gonter growl when he catches Old Ben’s throat,’ Sam said. ‘But he aint gonter never holler, no more than he ever done when he was jumping at that two-inch door. It’s that blue dog in him. What you call it?’

‘Airedale,’ the boy said.”

—William Faulkner, ‘The Bear’, Go Down, Moses, 1942.

a fine bright ruddy color

“He was four inches over six feet; he had the mind of a child, the heart of a horse, and little hard shoe-button eyes without depth or meanness or generosity or viciousness or gentleness or anything else, in the ugliest face the boy had ever seen. It looked like somebody had found a walnut a little larger than a football and with a machinist’s hammer had shaped features into it and then painted it, mostly red; not Indian red but a fine bright ruddy color which whisky might have had something to do with but which was mostly just happy and violent out-of-doors, the wrinkles in it not the residue of the forty years it had survived but from squinting into the sun or into the gloom of canebrakes where game had run, baked into it by the camp fires before which he had lain trying to sleep on the cold November or December ground while waiting for daylight so he could rise and hunt again, as though time were merely something he walked through as he did through air, aging him no more than air did.”

—William Faulkner, ‘The Bear’, Go Down, Moses, 1942.

that brown liquor

“There was always a bottle present, so that it would seem to him that those fine fierce instants of heart and brain and courage and wiliness and speed were concentrated and distilled into that brown liquor which not women, not boys and children, but only hunters drank, drinking not of the blood they spilled but some condensation of the wild immortal spirit, drinking it moderately, humbly even, not with the pagan’s base and baseless hope of acquiring thereby the virtues of cunning and strength and speed but in salute to them.”

—William Faulkner, ‘The Bear’, Go Down, Moses, 1942.

Banksy

the energy contained in this equation

“‘We need numbers, letters, maps, graphs. We need scientific formulas

to understand the structure of matter. E equals MC squared.’

He wrote the equation on the blackboard.

‘How is it that a few marks chalked on a blackboard, a few little

squiggly signs can change the shape of human history? Energy, mass,

speed of light. Protons, neutrons, electrons. How small is the atom? I

will tell you. If people were the size of atoms—think about it,

Gagliardi—the population of the earth would fit on the head of a pin.

Never mind the vast amounts of energy stored in matter. Matter.

Something that has mass—a solid, a liquid, a gas. Never mind what

happens when we split the atom and release this energy. Energy. The

capacity of a physical system to do work. I want to know how it is that

a few marks on a slate or a piece of paper, a little black on white, or

white on black, can carry so much information and contain such

shattering implications. Never mind the energy packed in the atom. What

about the energy contained in this equation? This is the real power.

How the mind operates. How the mind identifies, analyzes and

represents. What beauty and power. What marvels of imagination does it

require to reduce the complex forces of nature, all those unseeable

magical actions inside the atom—to express all this with a bing and a

bang on a black board. The atom. The unit of matter regarded as the

source of nuclear energy. The Greeks of the fifth century B.C. proposed

the idea of the atom. B.C., Miss Innocenti. Before Chewing Gum. Small,

small, small. Something inside something else inside something else.

Down, down, down. Under, under, under. Next time, chapter seven. Be

prepared for an oral quiz.’”

—Don DeLillo, Underworld, 1997.

Haydn’s ‘Surprise’ Symphony?

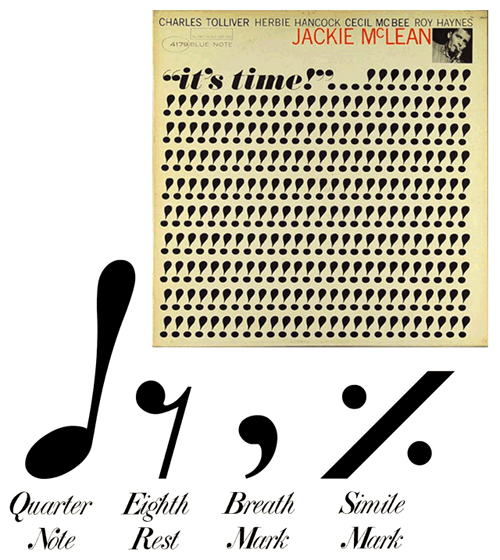

If an album’s emotionality can be quantified in exclamation points,

If an album’s emotionality can be quantified in exclamation points,

this recording by jazz saxophonist Jackie McLean seemingly defies

competition. The double quotation marks, apostrophe, ellipsis, and 244

exclamation points suggest the slanted lines and dots of music

notation. If we take the exclamation points to be quarter notes, this

‘score’ is one long tremolo (the rapid repetition of a single tone).

Notice that the score even has a time signature: ‘it’s time!’ Perhaps

the three dots of the ellipsis indicate three beats to a measure. In

any case, this album cover beautifully reminds us that there’s

punctuation in music and music in punctuation. (Album cover via www.gokudo.co.jp)

You don’t have to open your eyes

“‘Dad’s in the breezeway washing the car. Meanwhile way out here they

were putting troops in trenches for nuclear war games. Fireballs

roaring right above them.’

‘Positioned too close, you mean.’

‘That’s the story I hear. You look at your arm and

see right through it. Basically your arm becomes an x ray of your arm.

You can see right through the uniform cloth and the skin. The light’s

so white. You can see blood, bones and what not. But that’s not all.

You can see all this with your eyes shut. You don’t have to open your

eyes. You see right through the lids. Ha!’”

—Don DeLillo, Underworld, 1997.

white gone mad

“The dune fields, the alkali flats, the whiteness, the whole white sea-bottomed world, the lines of white haze in the distance, the six-thousand-year-old mummified baby found in a cave near White City, yes, and there were animals that bleached themselves white over the eons, a once-brown mouse that color-matched itself to the gypsum drifts to escape the gaze of predators.

The wind blew out of the Organ Mountains, busting up to fifty miles an hour, refiguring the dunes and turning the sky an odd dangerous gray that seemed a type of white gone mad.”

—Don DeLillo, Underworld, 1997.